The Elfin Ship by James P. Blaylock – Annotated Bibliography Entry

The following is a sample entry from A Comprehensive Dual Bibliography of James P. Blaylock & Tim Powers for The Elfin Ship by James P. Blaylock.

[113] The Elfin Ship, James P. Blaylock

A. _____, Del Rey – Ballantine Books, New York, NY. 1982. ISBN 0-345-29491-2. 8vo. Paperback advanced reading copy issued in pale green wraps. Only 3 or 4 copies produced.

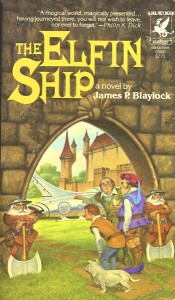

B. _____, Del Rey – Ballantine Books, New York, NY. August, 1982. ISBN 0-345-29491-2. 12mo. Paperback novel, published in wraps with cover art by Darrell K. Sweet.

C. Elfenschiff im Geistermeer, Goldman, Germany. February, 1987. ISBN 3-442-23907-9.

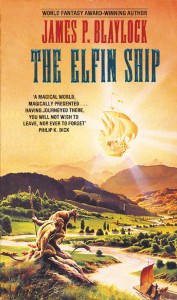

D. _____, Grafton, ondon, UK. 1988. ISBN 0-586-20172-6. 12mo. Paperback with cover art by Geoff Taylor.

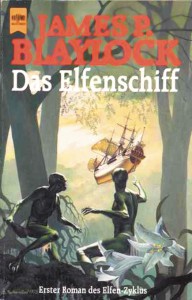

E. Das Elfenschiff, Heyne, Germany. 1994. ISBN 3-453-07794-6.

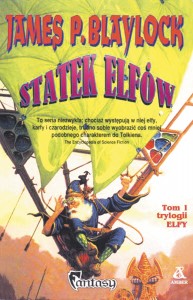

F. Statek Elfów, Amber, Warsaw, Poland, 1995. ISBN 83-7082-970-8. Translated by Radosław Januszewski.

G. Le Vaisseau elfique, Rivages, France. February, 1997. ISBN 2-743-60178-7. 8vo. Paperback with cover art that is a detail reproduced from a Victorian era fairy painting, created by Richard Dadd while he was committed to Bedlam. Translated by Pierre-Paul Durastanti.

H. Le Vaisseau elfique, J’ai lu, France. March, 2000. ISBN 2-290-30154-X. 12mo. Paperback.

I. Эльфийский корабль, Джеймс Блэйлок, St. Petersburg, Russia. 2003. ISBN 5-352-00568-2. Translated by E. Kleymenov.

This is a whimsical story of a cheesemaker, Jonathan Bing, who sets out on a quest to discover why trade to his river town has halted inconveniently right before the Winter holiday season. He and his friend, the Professor Wurzle, seek answers to the mystery, and they transport cheeses themselves to use in trade for dwarven cakes and children’s toys to take back to their village. Along the way, they run afoul of goblins masterminded by a nefarious dwarf, and they find surprising allies in the carefree Linkmen and elves.

Note that the character named “the Squire” or “Squire Myrkle”, was *not* named after Blaylock’s friend, Roy A. Squires. The “Squire” name was inspired by Blaylock’s reading of various humorous 18th and 19th century English novels, particularly Tristram Shandy and Dickens’s novels.

Blaylock thinks the “Myrkle” name was borrowed from a character in The Bank Dick, a W.C. Fields film that involves a blind man by that name who breaks up a general store with his cane.

Inspired by the whimsical nature of Blaylock’s work, I offer the following ridiculously pedantic examination of the possible sources of inspiration for the evil dwarf:

Blaylock has cited a handful of literary influences which likely played into the writing and story style of the Elfin Ship series, including Robert Louis Stevenson, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. Having noted that Blaylock read quite a bit of Victoriana in preparation for the Steampunk works such as Homunculus, and repeatedly seen turns of phrase that were clearly Victorian in origin, and Blaylock’s propensity to adopt unique names for characters similar to the habits of Charles Dickens, I assumed that he’d been influenced very heavily by many of the works of Dickens. One work in particular, I felt, must have been the source of the character of the villainous dwarf found in the Elfin Ship series – I discovered an evil dwarf, Daniel Quilp

, in Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop – who parallels Blaylock’s dwarf in a number of key ways including: smoking a pipe while peering balefully through the clouds of smoke; appearing near magically everywhere, to the horror of little Nell and her friends; acting in monstrous manner such as eating clams, shells and all, and gulping down boiling tea; acting frighteningly and abusively to keep control over his wife and her mother; and using his human agents, including particularly vile barristers, to launch his wicked conspiracies against the innocent. Dickens’ dwarf is a sort of living incarnation of the Punch character of Punch & Judy puppet shows, and eventually he dies by drowning in an accident, and when he later washes up was assumed to have been a suicide, and is finally buried at the center of a crossroads with a stake in his heart – a superstitious practice observed to insure that the ghost of a suicide will not walk the night, since consecrated ground was denied those who took their own lives – but, it’s nearly unnecessary to point out that crossroads and staking in the heart are also used to stop other certain supernatural creatures, and this fate just goes to highlight how the dwarf was so successfully malevolent as to have been perceived as having near-magical abilities in that respect. It seemed very likely to me that Blaylock must’ve been inspired by Dickens’ dwarf – after all, where else could you find such an unusual mixture of two-dimensional evil made all the more horrifying by being slightly ludicrous? There are a handful of congruencies betwixt the two characters that would seem to defy mere coincidence. Yet, when I attended VCon in Vancouver in 2002, I put forth this theory to Blaylock, and he adamantly denied having ever even read The Old Curiosity Shop, by Dickens. Blaylock is in no wise prone to dishonesty of any sort, but I’m still very floored by some of the similarities of the two characters. I believe Blaylock, but I still cannot help wondering if he was exposed to the Quilp character and just doesn’t recall the chance exposure. Perhaps he could’ve heard a lecture on the work while attending college in the English Department at Fullerton? Perhaps he thumbed through a Cliff’s Notes on the Dickens classic at some point? Perhaps he read a commentary on it? He definitely read The Pickwick Papers by Dickens, and The Old Curiosity Shop was published in a serial publication just like Pickwick Papers were – it’s not unreasonable to think that he could have been exposed to the dwarf somewhere in a critical examination of Dickens’ works and it stuck in his subconscious. Read the two works and compare the respective dwarves – then, let you be the judge!

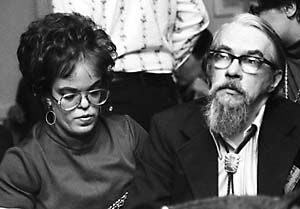

Objectively, I must also point out that there are many other tales out there which include villainous dwarves as well. European fairytale mythology is rife with references to dwarves and other wee folk, and the tales are not all flowers and sunlight – the fey dwarves are wicked at least as often as good. But, we don’t even have to go back that far to find sources of inspiration for the dwarf character that are definitely not Dickensian in nature. Blaylock used to live in an apartment with a family of little people as neighbors, it seems. Powers retells a story wherein he went to Blaylock’s one morning and was reading something when he leaped up with a shout and slammed the living room curtains shut – he says that Blaylock hadn’t told him of his dwarvish neighbors and suddenly they were all outside the window, playing in the swimming pool, utterly astounding Powers. Powers thought at first it was some convoluted joke perpetrated on him by Blaylock, but it was actually just chance instead of conspiracy.

So, Blaylock may’ve just been inspired by his neighbors to create the villain in The Elfin Ship. There’s nothing like living in the same apartment building with someone to make them transform before your very eyes into an evil villain. Or, his inspiration could’ve been the traditional European folklore sources. I’m still confounded by the facts that Blaylock cites Dickens as one source of inspiration while the similarities betwixt Dickens’ Quilp and Blaylock’s Selznick seem significant, contrasted with Blaylock’s assertion that he never read this Dickens work. If Quilp was a source inspiration, it must have been accidental or subconscious, I guess.

Blaylock confirms that he was made aware of the superficial elements of The Old Curiosity Shop through the courses he took in literature, but the influence would have only been very slight and wouldn’t involve any specifics. He states that during this time, both he and Powers were “mildly insistent” about including dwarves in pieces they wrote — so much so that for years they referred to this as “the dwarf dilemma”. (Their friends must’ve been aware of this as well — see the notes for Dean Koontz’s book, Strangers, in the Related Books section.)

The Elfin Ship was originally written in a substantially different format when first submitted to the publisher. The editor, Lester Del Rey, recommended changes to make the plot work better, so that the goal that was outlined at the beginning of the story of delivering cheeses and bringing back elfin toys and cakes to Twombly Town would actually end up happening. The original version of the work was later published by Subterranean Press (see The Man in the Moon entry later in this section).

In a funny twist of coincidence, Lester Del Rey’s last wife, Judy Lynn Del Rey, was a person of short stature – a dwarf, that is, and one can only wonder what crossed their minds as they received these manuscripts wherein the villain is the Dwarf. Initially, Lester was Blaylock’s editor, and Judy-Lynn took over somewhere down the line. It could be easy to assume that Del Rey’s initial dislike of the book could have arisen from consciously or subconsciously insulted animosity to the portrayal of a dwarf as a villain, but this cannot at all be assumed. Del Rey’s rejection appears to have been based solely upon professional considerations that the plot as submitted would not have been appreciated by readers and wouldn’t be commercially successful in the long run. When rewritten, Del Rey ultimately published the book and its sequel. Both Blaylock and Powers appreciated the criticism Del Rey provided to them, and took it as coaching. Both authors have stated that they profited from it and improved their writing as a result.

Overall influences for the Elfin Ship series have been cited as The Wind in the Willows, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Lud-in-the-Mist. (See entry in Related Books section for Lud-in-the-Mist.)

Note that the protagonists of Elfin Ship stayed at an inn named “The Cap’n Mooneye” in the city of Seaside. The namesake of the inn is the character and namesake of the poem, “Mooneye Agonistes” found in the On Pirates book and in the Poetry Fullerton 3 periodical.

Trackbacks

There are no trackbacks on this entry.

Comments

There are no comments on this entry.